Jul 22, 2018

How Big is the World? [EZLN]

After a day of preparation meetings for the Other Campaign (it was September, it was dawn, there was rain from a far-off cloud), we were heading towards the hut where our things were when we ran into a citizen who all of a sudden came out with: “Listen, Sup, what are the Zapatistas proposing?” Without even stopping, I answered: “Changing the world.” We reached the hut and began getting things ready in order to leave. Insurgenta Erika waited until I was alone. She approached me and said “Listen, Sup, the world is very big,” as if she were trying to make me realize what nonsense I was proposing and that I didn’t, in reality, know what I was saying when I’d said what I’d said. Following the custom of responding to a question with another question, I came out with: “How big?“

After a day of preparation meetings for the Other Campaign (it was September, it was dawn, there was rain from a far-off cloud), we were heading towards the hut where our things were when we ran into a citizen who all of a sudden came out with: “Listen, Sup, what are the Zapatistas proposing?” Without even stopping, I answered: “Changing the world.” We reached the hut and began getting things ready in order to leave. Insurgenta Erika waited until I was alone. She approached me and said “Listen, Sup, the world is very big,” as if she were trying to make me realize what nonsense I was proposing and that I didn’t, in reality, know what I was saying when I’d said what I’d said. Following the custom of responding to a question with another question, I came out with: “How big?“

She kept looking at me, and she answered almost tenderly: “Very big.”

I insisted: “Yes, but how big?”

She thought about it for a minute and said: “Much bigger than Chiapas.”

Then they told us we had to go. When we had gotten back, in the barracks now and after making Penguin comfortable, Erika came over to me, carrying a globe, the kind they use in elementary schools. She put it on the ground and told me: “Look, Sup, here, in this little piece, there’s Chiapas, and all this is the world,” almost caressing the globe with her dark hands as she said it.

“Hmm,” I said, lighting my pipe in order to gain some time.

Erika insisted: “Now you’ve seen that it’s very big?”

“Yes, but we’re not going to change it all by ourselves, we’re going to change it with many compañeros and compañeras from everywhere.” At that point they called the guard. Showing that I’d learned, she shot back at me before she left: “How many compañeros and compañeras?”

How big is the world?

In the Tehuaca’n valley, in the Sierra Negra, in the Sierra Norte, in the suburban areas of Puebla. From the most forgotten corners of the other Puebla, answers are ventured:

In Altepexi, a young woman replied:

More than 12 hours a day of work in the maquiladora, working on days off, no benefits, or insurance, or Christmas bonus, or profit sharing. Authoritarianism and bad treatment by the manager or line supervisor, being punished by not being paid when I get sick, seeing my name on a black list so they won’t give me work in any maquiladora. If we mobilize, the owner closes down and goes someplace else. Transportation is very bad, and I get back to the house where I live really late. I look at the light bill, the water bill, taxes, I do the sums and see there’s not enough. Realizing that there’s not even any water to drink, that the plumbing doesn’t work and that the street stinks. And the next day, after sleeping badly and being poorly fed, back to work. The world is as big as the rage I feel against all this.

A young Mixtec indigenous:

My papa went to the United States more than 12 years ago. My mama works sewing balls. They pay her 10 pesos for each ball, and if one of them isn’t good, they charge 40 pesos. They don’t pay then, not until the contractor comes back to the village. My brother is also packing to leave. We women are alone in this, in carrying on with the family, the land, the work. And so it’s up to us to also carry on with the struggle. The world is as big as the courage this injustice makes me feel, so big it makes my blood boil.

In San Miguel Tzinacapan an elderly couple look at each other and answer almost in unison:

the world is the size of our effort to change it.

An indigenous campesino from the Sierra Negra, a veteran of all the dislocations, except the dislocation of history:

It has to be very big, that’s why we need to make our organization grow.

In Ixtepec, Sierra Norte:

The world is the size of the swinishness of the bad governments and of the Antorcha Campesina, which is just prejudiced against the campesino and is still poisoning the earth.

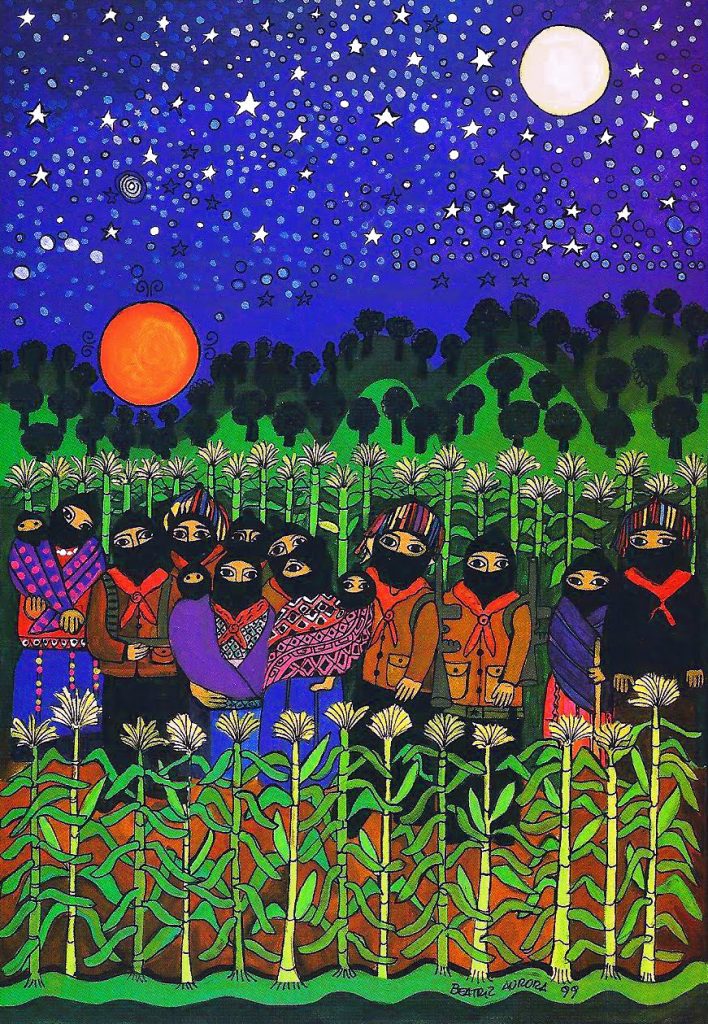

In Huitziltepec, from a small autonomous school, a rebel television station is broadcasting a truth:

The world is so large that it has room for the history of the community and of its desire and struggle to continue looking out at the universe with dignity. A lady, an indigenous artisan, from the same round as the departed Comandanta Ramona, adds off-mike: “The world is as big as the injustice we feel, because they pay us a pittance for what we do, and we watch the things we need just pass us by, because there’s not enough.”

In the neighborhood of Granja:

It can’t be very big, because it seems as if there’s no room for poor children, they just scold us, persecute and beat us, and we’re just trying to make enough to eat.

In Coronango:

As big as the world is, it’s dying from the neoliberal pollution of the land, water, air. It’s breaking down, because that’s what our grandparents said, that when the community breaks down, the world breaks down.

In San Mati’as Cocoyotla:

It’s as big as the government’s lack of shame, which is simply destroying what we do as workers. Now we have to organize in order to defend ourselves from the government which is supposed to serve us. Now they see that they are without shame.

In Puebla, but in the other Puebla:

The world isn’t so big because what the rich already have isn’t enough for them, and now they want to take away from us poor people what little we have.

Again, another Puebla, a young woman:

It’s very big, so just a few of us can’t change it. We all have to join together in order to do it, because if not, we can’t, you get tired.

A young artist:

It’s big, but it’s rotten. They extort money from us for being young people. In this world it’s a crime to be young.

A neighbor:

However big it may be, it’s small for the rich, because they are invading communal lands, ejidos, popular neighborhoods. As if there’s no longer room for their shopping centers and their luxuries, and they’re putting them on our lands. The same way, I believe, that there’s no room for us, those of below.

A worker:

The world is as big as the cynicism of the corrupt leaders. And they still say they’re for the defense of the workers. And up above they’ve got their shit together: whether it’s the owner, the official or the pro-management union leader, no matter what new things they say. They should make one of those landfills, a garbage dump, and put all of them in it together. Or not, better not, because they’d certainly pollute everything. And then if we were to put them in jail, the criminals would riot because even they don’t want to live next to those bastards.

Now it’s dawn in this other Puebla which hasn’t ceased to amaze us with every step we take on its lands. We’ve just finished eating, and I’m thinking about what I’m going to say on this occasion. Suddenly a little suitcase is sticking out from under the door, and it almost immediately gets stuck in the crack. A murmur of heavy breathing can barely be heard, of someone pushing from the other side. The little suitcase finally makes it through and, behind it, stumbling, something appears which looks remarkably like a beetle. If it weren’t for the fact that I was in Puebla, albeit the other Puebla, and not in the mountains of the Mexican southeast, I would almost swear that it was Durito. As if putting aside a bad thought, I return to the notebook where the question which headed this surprise exam is already written down. I continue trying to write, but nothing worthwhile occurs to me. That is what I was doing, making a fool of myself, when I felt as if something were on my shoulder. I was just about to shrug in order to get rid of it, when I heard:

“Do you have tobacco?”

“That little voice, that little voice,” I thought.

“What little voice? I see you’re jealous of my masculine and seductive voice,” Durito protested.

There was no longer any room for doubt, and so, with more resignation than enthusiasm, I said:

“Durito…!”

“Not ‘Durito’! I am the greatest righter of wrongs, the savior of the helpless, the comforter of the defenseless, the hope of the weak, the unattainable dream of women, the favorite poster of children, the object of men’s unspeakable jealousy, the…”

“Stop it, stop it! You sound like a candidate in an election campaign,” I told Durito, trying to interrupt him. Uselessly, as can be seen, because he continued:

“…the most gallant of that race which has embraced knight errantry: Don Durito of the Lacandona SA of CV of RL. And authorized by the good government juntas.”

As he said this, Durito showed me a decal on his shell which read: “Authorized by the Charlie Parker Rebel Zapatista Autonomous Municipality (MAREZ).”

“Charlie Parker? I didn’t know we had a MAREZ with that name, at least we didn’t when I left,” I said disconcertedly.

“Of course, I established it just before I left there and came to your aid,” Durito said.

“How odd, I asked them to send me tobacco, not a beetle,” I responded-protested.

“I am not a beetle, I am a knight errant who has come to get you out of the predicament you have found yourself in.”

“Me? Predicament?”

“Yes, do not act like Mario Marín’s “precious hero” in the face of those recordings which revealed his true moral caliber. Are you in a predicament or not?”

“Well, predicament, what’s called a predicament, then…yes, I’m in a predicament.”

“You see? Perhaps you were not longing for me, the very best of the knights errant, to come to your aid?”

I thought for barely an instant and responded:

“Well, the truth is, no.”

“Come, do not conceal that great pleasure, the huge joy and the unbridled enthusiasm which exists in your heart upon seeing me once again.”

“I prefer to conceal it,” I said resignedly.

“Fine, fine, enough of the welcoming fiestas and fireworks. Who is the scoundrel I should defeat with the arm I have below and to the left? Where are the Kamel Nacif, Succar Kuri so-and-sos and others of such low ilk?”

“No scoundrels and nothing to do with that ilk of swine. I have to answer a question.”

“Come on,” Durito pressed.

“How big is the world?” I asked.

“Well, there is a short version and a long version of the answer. Which do you want?”

I looked at my watch. It was 3 AM, and my eyelids and cap were falling into my eyes, and so I said without hesitation:

“The short version.”

“What do you mean, the short version! Do you think I have been following your tracks through eight states of the Mexican Republic in order to present the short version. Naranjas podridas, ni mais palomas, not hardly, absolutely not, no way, negative, rejected, no.”

“Fine,” I said, resigned. “The long version then.”

“That’s it, my big-nosed nomad! Take this down.”

I picked up my pen and notebook. Durito dictated:

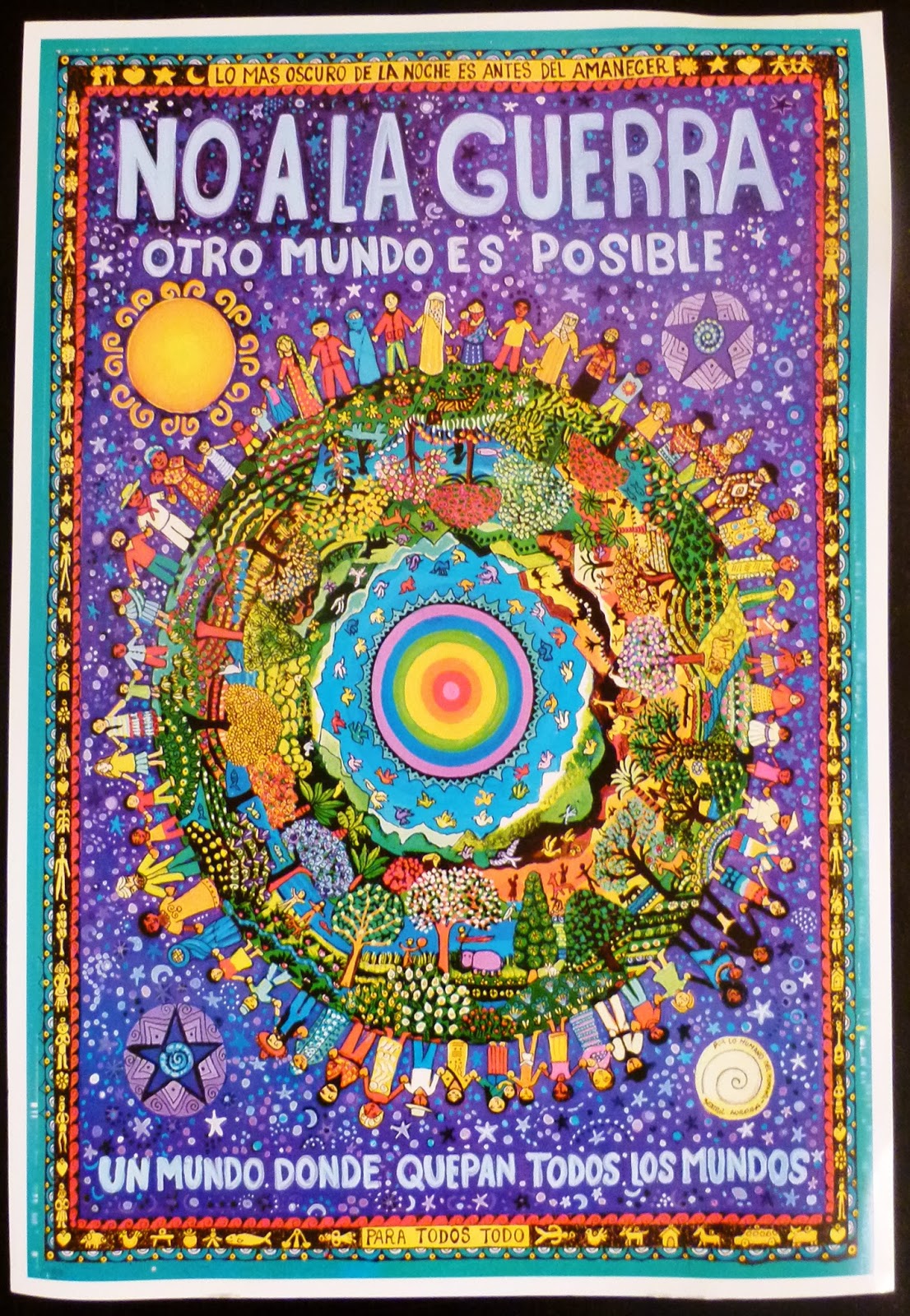

“If you look at it from above, the world is small and the color green of the dollar. It fits perfectly in the price indexes and the valuations of a stock market, in the profits of a transnational, in the election polls of a country which has suffered the hijacking of its dignity, in the cosmopolitan calculator which adds capital and subtracts lives, mountains, rivers, seas, springs, histories, entire civilizations. Seen from above, the world is very small because it disregards persons and, in their place, there is a bank account number, with no movement other than that of deposits.

But if you look at it from below, the world stretches so far that one look is not enough to encompass it, instead many looks are necessary in order to complete it. Seen from below, the world abounds in worlds, almost all of them painted with the color of dislocation, poverty, despair, death. The world below grows sideways, especially to the left side, and it has many colors, almost as many as persons and histories. And it grows backwards, to the history which the world below made. And it grows towards itself with the struggles that illuminate it, even though the light from above goes out. And it sounds, even though the silence of above crushes it. And it grows forward, divining in every heart the morrow that will be given birth by those who below are who they are. Seen from below, the world is so big that many worlds fit, and, even so, there is space left over, for example, for a jail.

Or, in summary, seen from above, the world shrinks, and nothing fits in it other than injustice. And, seen from below, the world is so spacious that there is room for joy, music, song, dance, dignified work, justice, everyone’s opinions and thoughts, no matter how different they are if below they are what they are.”

I had barely been able to write it down. I re-read Durito’s response, and I asked him:

“And what is the short version?”

“The short version is the following: the world is as big as the heart which first hurts and then struggles, along with everyone from below and to the left (where the heart is).”

Durito left. I continued writing while the moon waned in the heavens with the night’s damp caress…

I would like to venture a response. Imagining that I, with my hands, undo her hair and her desire, that I envelope her ear with a sigh, and, while my lips move up and down her hills, understanding that the world is as large as is my thirst for her belly.

Or, more decorously, trying to say that the world is as large as the delirium to make it “otherly,” as the ear that is needed to embrace all the voices of below, as this other collective desire to go against the tide, uniting rebellions of below, while above they separate solitudes.

The world is as big as the prickly plant of indignation which we raise, knowing the flower of tomorrow will be born from it. And, in that tomorrow, the Iberoamerican University will be a public, free and secular university, and in its corridors and rooms will be the workers, campesinos, indigenous and others who today are outside.

That is all. Your responses should be presented on February 30 in triplicate: one for your conscience, another for the Other Campaign and another with a heading that clearly states: Warning, for those of above who believe, naively, that they are eternal.

From the other Puebla.

Sup Marcos Sixth Committee of the EZLN Mexico, February of 2006 Originally published in Spanish by the Sixth Committee of the EZLN