Mar 23, 2016

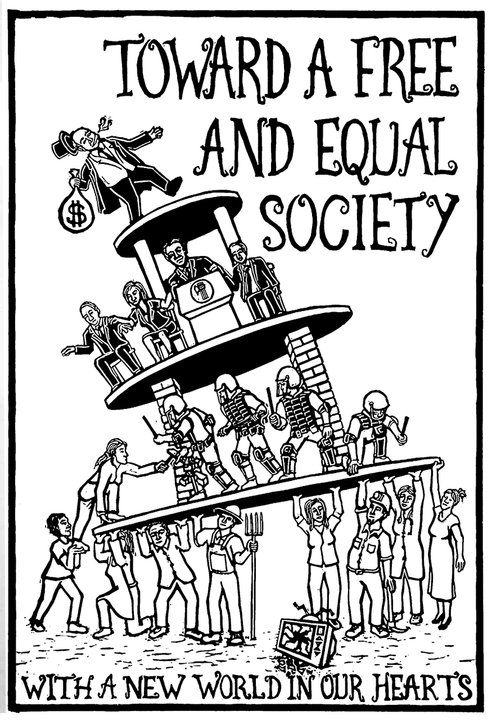

Anarchist Work Groups and 1-to-3 Organising

The essence of anarcho-syndicalism is shop-floor & neighbourhood level organising; the setting up of work groups that lay the basis for taking action to defend and extend our interests, and countering the drudgery and maddening pace of the global-work machine. These groups aim to be at once economic (based on shared material conditions) and political (based on shared political ideas). The setting up of work-groups is foundational in reigniting unionism as a pledge of solidarity among fellow-workers and in shaping broader resistance at the sites of power where we experience exploitation and hierarchy most directly. It’s important at this stage to note that regardless of whether people identify formally with anarcho-syndicalism or not, what matters is putting basic anarcho-syndicalist methods into practice, ie; our organisations, whether fluid, temporary or permanent, should ideally be controlled by the base, ultra democratic through the use of delegates and open assemblies regardless of official trade-union membership, direct-action orientated and be against intermediaries or organising methods which remove power from our hands.

The essence of anarcho-syndicalism is shop-floor & neighbourhood level organising; the setting up of work groups that lay the basis for taking action to defend and extend our interests, and countering the drudgery and maddening pace of the global-work machine. These groups aim to be at once economic (based on shared material conditions) and political (based on shared political ideas). The setting up of work-groups is foundational in reigniting unionism as a pledge of solidarity among fellow-workers and in shaping broader resistance at the sites of power where we experience exploitation and hierarchy most directly. It’s important at this stage to note that regardless of whether people identify formally with anarcho-syndicalism or not, what matters is putting basic anarcho-syndicalist methods into practice, ie; our organisations, whether fluid, temporary or permanent, should ideally be controlled by the base, ultra democratic through the use of delegates and open assemblies regardless of official trade-union membership, direct-action orientated and be against intermediaries or organising methods which remove power from our hands.

The following will outline one example (my own) of the nuts and bolts of this kind of organising in practice, set in the workplace. This will be accompanied by anarcho-syndicalist lessons/writings/ideas put forward by the Waiters Union (WU), Brisbane Solidarity Network (BSN), Solidarity Federation (SolFed) and the Industrial Workers of the World Recomposition Group (IWW) which I found helpful.

“We cannot wait to act until popular political viewpoints recognize revolutionary anti-capitalism as a valid and legitimate political position. If the political landscape is going to be altered radically, it is going to be altered by the self-directed activity of the working class. As militants, our role is to actively build an organization, a movement, a concept, that encourages and allows this class activity to flourish.”

“…the class-collaborationist unions – are falling increasingly out of favour. Working people are searching for alternatives now seemingly more than ever.”

IN THE BEGINNING:

It’s important to note that in some workplaces, particularly in production, there’s a state of constant agitation and actions burst out before committees ever get built. In other workplaces agitation just never seems to take hold. Once you’ve landed a job, it’s tempting to jump right into agitating and educating co-workers. This approach is problematic for several reasons. Experience has shown that workers who do not first build relationships are apt to be quickly labelled as an arrogant and disgruntled employee by management and gain a reputation among co-workers as a “complainer” and/or just another naive “crazy radical.”

Depending on the workplace it’s generally a good rule of thumb to allow yourself 3-6 months to get acquainted with the social landscape at your new job. During this time, organising consists of getting to know as many names and faces as possible, social mapping, building positive relationships with everybody, including management and co-workers that you may find personally repulsive. While organising under the radar, having enemies only makes things harder, whether those enemies are worthy of ire or not. You’ll have to get used to putting yourself out there and getting out of your comfort zones. Learning active listening skills and getting a diary can turn a flaky person into a solid organiser.

Building a reputation as a worker who carries their load, being someone who doesn’t over-commit and under-deliver, helps others, covers shifts, arrives on time and doesn’t call out sick frequently is another critical element of being taken seriously and establishing credibility. Working hard and doing a ‘good job’ may increase the rate at which you’re exploited, but it also makes the labor process easier for other workers, and they will take notice.

As one boss said to an organiser, ‘you’re a good worker but a bad employee’ – this sums up perfectly the situation good organisers often find themselves in.

There’s a lot to be said at this stage, for one, it’s important to hold your own agenda lightly.

As revolutionaries we (should be) brimming with ideas and excitement. A result of this is that we can sometimes get overly attached to projects that we want to create (eg: an action plan, a piece of text etc), to the point where we experience offence, anger, frustration etc if things don’t go exactly how we want. It’s easy to imagine the perfect project or action by ourselves and then try and push for this to happen. Being organised in a group isn’t easy though. In reality we’re always dealing with complexity – whether in people or ideas, and things don’t always go the way we want. ‘Holding our agenda lightly’ means having a mature predisposition towards being flexible and open-ended in the ideas we put forward, in a way where we value the collective process over the ‘end result’, and aren’t destroyed if our individual plan doesn’t go ahead exactly how we want it to.

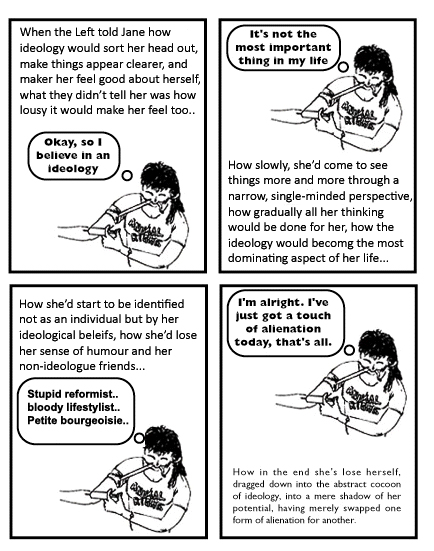

We need to move away from models of organising by lecturing people about why capitalism is horrible, assuming people are empty vessels devoid of political ideas or believing that getting people agitated will automatically lead to organisation because the workers are already radical. We don’t want to recreate the Left that treats people like trophies to win to an Ideology – the dogma with all the answers. Instead we need to think about organising as a relationship, a back and forth between a revolutionary(ies) and their co-workers in dialogue and common struggle. While laying out your own ideas is appealing and often satisfying, depositing ideas into people most often leads to a speedy withdrawal. Instead we want people to develop their own revolutionary ideas as part of their process about thinking about their experiences. As an organiser you try to get people to lay out their conception of their work, bosses, coworkers, and the world. Organisers work on what people want to work on, and the fights that they have interests in. It’s on this basis that people learn and develop, and through struggle that they radicalise. Addressing their interests in the context of collective struggle gives us the space to re-examine theories and ideas, and change them to fit new circumstances. That back and forth between ideas and actions is called praxis.

We need to move away from models of organising by lecturing people about why capitalism is horrible, assuming people are empty vessels devoid of political ideas or believing that getting people agitated will automatically lead to organisation because the workers are already radical. We don’t want to recreate the Left that treats people like trophies to win to an Ideology – the dogma with all the answers. Instead we need to think about organising as a relationship, a back and forth between a revolutionary(ies) and their co-workers in dialogue and common struggle. While laying out your own ideas is appealing and often satisfying, depositing ideas into people most often leads to a speedy withdrawal. Instead we want people to develop their own revolutionary ideas as part of their process about thinking about their experiences. As an organiser you try to get people to lay out their conception of their work, bosses, coworkers, and the world. Organisers work on what people want to work on, and the fights that they have interests in. It’s on this basis that people learn and develop, and through struggle that they radicalise. Addressing their interests in the context of collective struggle gives us the space to re-examine theories and ideas, and change them to fit new circumstances. That back and forth between ideas and actions is called praxis.

Good organising is preparing the field so that we can weather the storms that come not in 1 or 2 years, but in 10 or 30 years. This requires not just building actions, but creating new people, new protagonists in struggle. As Sam Dolgoff said,

“We must not be impatient. We must be prepared to work within the context of a long-range perspective which may take years of dedicated effort before visible progress will show that our struggles have not been in vain.”

We have to remember most people face this world completely alone, and feel terror at grappling with all the pressures and insecurities to themselves and their families thrown at them. Even just to walk with someone down that path, and have someone listen to them and present alternatives can be powerful. We’ve been raised in a society that has socially engineered isolation and anti-social behaviours for decades, and we are swimming against the tide to try and build lived mutual-aid and solidarity in our day to day activities. Any steps we can take to back others up can create tiny ruptures and open up new spaces for reflection, sustenance and action.

2. Agitate, Educate, Organise: Workplace Mapping

Business-Union training around workplace mapping usually revolves around recruitment – ie who is an activist, who is hostile to the union, who is a potential member, who can help out with campaign & election work and hand out trade-union material etc. The workplace mapping we’re more interested in is around class & relationships, or in more everyday terms who’s a grub, who seems solid, what levels of management can be pressured into leverage, what  issues people think are important etc. We’re looking for fellow workers who have a natural aversion to bosses and some level of class awareness, even if its not articulated as such (ie realises the difference between bosses and workers, sticks up for workmates etc). A grub on the other hand is someone who’s just in it for themselves, usually a bad worker (but a good employee), sucks up to the boss, likely to scab if given the chance, dobs into the boss etc, ie; someone who’s hostile to union organising.

issues people think are important etc. We’re looking for fellow workers who have a natural aversion to bosses and some level of class awareness, even if its not articulated as such (ie realises the difference between bosses and workers, sticks up for workmates etc). A grub on the other hand is someone who’s just in it for themselves, usually a bad worker (but a good employee), sucks up to the boss, likely to scab if given the chance, dobs into the boss etc, ie; someone who’s hostile to union organising.

“Workplace organising is about seeing the volcano inside your fellow workers’, fanning the flames and creating a culture of class solidarity in your workplace, whether its articulated concretely like this or not. This culture is anti-boss, pro-worker and generally follows this path to its logical conclusion; that of a systemic analysis of capitalism and organisational forms which operate above and over the people. This is what we call anarcho-syndicalist workplace organising, although what matters is not that people self-identify with anarcho-syndicalism (although we don’t see it as a bad thing), but that people identify with anarcho-syndicalist methods. Part of that culture already exists in some form, and solidarity will always be present in any workplace, but for those jobs in which division seems rife, organising necessarily demands that we do more than just integrate ourselves into existing social dynamics, and instead take the initiative to create our own. Sometimes this means as little as engaging with groups of workers where there would normally be no interaction, even at the risk of seeming awkward. Other times it might involve ruining the credibility of bosses with a high degree of social power amongst the workers. We must be prepared to work with the terrain that we are given, but also be willing to shape that terrain to make it more accommodating.”

“Workplace organising is about seeing the volcano inside your fellow workers’, fanning the flames and creating a culture of class solidarity in your workplace, whether its articulated concretely like this or not. This culture is anti-boss, pro-worker and generally follows this path to its logical conclusion; that of a systemic analysis of capitalism and organisational forms which operate above and over the people. This is what we call anarcho-syndicalist workplace organising, although what matters is not that people self-identify with anarcho-syndicalism (although we don’t see it as a bad thing), but that people identify with anarcho-syndicalist methods. Part of that culture already exists in some form, and solidarity will always be present in any workplace, but for those jobs in which division seems rife, organising necessarily demands that we do more than just integrate ourselves into existing social dynamics, and instead take the initiative to create our own. Sometimes this means as little as engaging with groups of workers where there would normally be no interaction, even at the risk of seeming awkward. Other times it might involve ruining the credibility of bosses with a high degree of social power amongst the workers. We must be prepared to work with the terrain that we are given, but also be willing to shape that terrain to make it more accommodating.”

“Building class solidarity is a dialectical process. Within the workforce, an organiser should seek to eliminate divisions that hinder class solidarity like racism, sexism etc by engaging across barriers delineated by those dynamics. This takes the form of easing into informal cliques that form during breaks, attending and arranging social functions that include diverse groups of workers, and generally refusing to accept to conform to constructs that hinder solidarity. We must facilitate the seamless weaving together of the disparate social groupings that make up our work site.”

Creating a class-conscious culture at work also means that we learn to see organising at home and in the community–with co-workers–as a natural and necessary part of organizing on the job. The working class holds its power at the point of production, but our organising, i.e. our relationships to our co-workers, can’t be limited to the confined issues and dynamics of the job site. Ruling class exploitation extends far beyond the walls of the factory, the coffee bar, the office and the waterfront. The more we can show solidarity on a level that illustrates our relationship to one another as members of the working class (e.g. visiting co-workers on disability, helping them raise money to replace a stolen bike or to purchase a plane ticket to visit a deceased relative, offering to help out with childcare, etc.), drawing a connection between the reality of the wage system and the myriad effects which contribute to our collective misery, the more we can contribute to the building of an anti-authoritarian, non-hierarchical working class movement.

“Effective networking involves more than establishing a credible local identity as a neighbour it means being a neighbour. that takes a lot of time – time many of us never seem to have. We always seem to be too busy to be neighbourly. We have to make time. it is a constant struggle to make sure that we are not too busy to be neighbourly. All the things once learned at an easier pace which allowed stopping, talking, reflecting are passed by. We travel so much faster than our senses were designed for, and much that speeds by is lost to us, drowned in the white noise of modern life.”

Workplace mapping is a useful tool, both in practicing to keep a journal to later evaluate experiences and in purposeful relationship building. Keeping all this information locked up in your head is nearly impossible. The taking of daily notes on the interactions you have with co-workers will prove indispensable when you want pass on that information or simply organise your own thoughts into a clearer social map. Check with fellow organisers as to how they keep their notes in order so that you can devise a system that best fits your own situation.

Getting your 1-to-3

One-to-Three organising is based on the ‘community organising training’ given by the Waiters Union, who orientate their action towards creating neighbourhood networks based on mutual-aid and ‘houses of hospitality’.

So what do we mean getting a 1-to-3 going? It’s not an original idea but it’s a useful basic concept that gives you a stable foundation to work from, upon which further organising will be easier and clearer.

The Waiters Union sum the 1-3 organising idea up nicely:

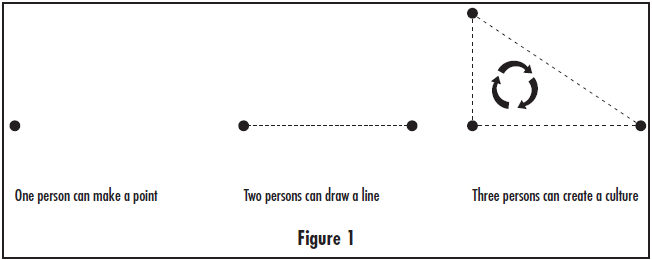

One person alone has no relationships Two people have one relationship But Three people have three relationships

One person can think about a concept/idea Two people can discuss an idea But three people can turn that idea into reality

One person alone can make a point Two people can draw a line

But three people can make a space and culture to invite others into

– A space through which you can incarnate an alternative and invite others to experience that alternative.

Basically, we need to find at least two other supporters in order to develop a culture; Having three people onboard is the bare bones minimum needed to go ahead with an organising drive. A good reason to start with getting your 1-to-3 is that it shields you from going ahead with ideas that possibly aren’t that great or grounded in reality, which even the best of us can fall into from time to time. Generally if you can create a 1-to-3, it means the angle of your project/organising drive has some good points and that you will have a strong foundation to work from. This is in direct contrast to one organiser doing everything by themselves and then expecting others to be drawn into it (the bizarre ‘build it and they will come (or we’ll make it up)’ model that permeates a lot of organising activity in australia).

On a side note, the Solidarity Network model similarly offers one effective way of supporting workplace/housing struggles and initiating organising drives in areas where you have no strategic base. Again, this is in direct contrast to the ‘build it and they will come model’ (eg: organising a wage increase drive for fast food workers and then expecting them to sign up to it via website).

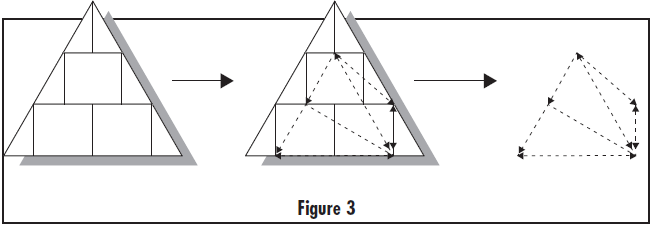

Once you get your 1-to-3, the next step is to take that culture outside of the battlefield (work) and let it germinate (fig 3) before bringing it back inside.

When I started working at a new care-work company two years back there were no links between workers, we were isolated and split into different sections (cleaners, front desk staff, support staff, care-work staff, security staff etc). Workers frequently were made to take on work that was not on their job description including ridiculous and dangerous tasks. Workers were fired and we did not learn why. We were spoken individually to by management. Straight off the bat I noticed section of foreign workers employed for a specific job were frequently working shifts that went between 12-16 hours, occasionally more. There was no official trade-union membership (apart from myself) and they offered nothing in terms of assistance, as usual, operating more like a service delivery organisation or representative NGO (though I still tried to encourage peeps to join).

I made an effort to get to know everyone at the workplace and became good mates with many of the people there. I started mapping the place out and found that pretty much the majority of workers had grievances that were worth forming solidarity and potentially organising around. In particular, I built enough trust with the section of foreign workers to learn that they were (unofficially) being paid less than minimum wage cash in hand and were knowingly (by management) being exploited by their subcontractor (the boss was asking for $30,000 under the table to provide a permanent residency letter – basically indentured labour).

From here I worked on getting a 1-to-3 going. I identified one work-mate who was involved with the waiters union, and one work-mate who had community organising experience in his home country (India). We slowly broke down barriers between different workers regardless of what sub-contracted organisation they were employed by, had lots of 1-1′s, shared information with each other – and what used to be glances of recognition turned into solid chats.

We all became good mates and grievances became a frequent topic – lunch breaks were utilised between different workers to relay information (‘the workers telegraph’). One worker suggested we should meet up outside of work to have a proper discussion and clear the air around what’s been happening and alleged grievances – something I was aiming towards anyway.

We had a BBQ in Kangaroo Point, these BBQ’s turned into regular events, sharing Indian food, shisha, beers etc. The key point is that these weren’t just social events, but had an extra intentional political character with an organising focus; a few people still kept their ‘organiser’ hats on even though they were having fun. I started handing out organising material/articles from Brisbane Solidarity Network relating to the industry we worked in (care work) including ‘Crisis: Ipswich—Brisbane‘ – a handbook written by support workers containing both practical info and politics (which despite not being updated for 4 years is still used as a default resource by a few agencies). This developed into a semi-informal, irregular discussion/reading group, where even if not everyone read the articles, at least some of the social event would focus on the article and everyone chipped in their two cents.

Over a year period various topics and articles were discussed. A highlight being the discussion of workplace theft after it came out that lots of people were racking things from work. We discussed both time theft (taking extra breaks, making the job easier) and overt theft (racking goods) and how they justified it. Usually this justification had a political nature (the boss is making us do all this overtime, they waste so much stuff anyway etc). Also overt was discussion around the class nature and root causes of various social issues which the organisation we worked for was involved in.

A fellow worker set up a private facebook group (‘workmates’) and although this was mainly used to post memes, cat pictures etc it was occasionally used to continue workplace discussions. Someone made a logo for the group which was probably its only step towards formality – badges were also considered! At one stage a new worker who we’d taken into the fold was added to this group and invited one of the people we identified as a grub. We freaked out at this stage thinking that he’d snitch but fortunately there was no drama.

During the entire organising drive, I utilised organisers involved with Brisbane Solidarity Network as a sounding board to share notes and ideas, gain support and confidence in what I was doing and explore possible ways forward. This organising process drastically changed the feeling at work, and although there were no grievances reaching boiling point at this stage, it made being at work that little bit more bearable, occasionally even enjoyable as we brought in food for each other and played cat and mouse games with the bosses. More important it paved the way for a better response when issues did begin to surface.

For example:

- We were able to have a coordinated response in resisting work speed-ups and some of the more ridiculous work, instead of just shirking it as individuals. For example, there was a new rule imposed that we had to call management every time a certain incident occurred, effectively taking away our autonomy and ability to use discretion in our decision making. We made sure to call everytime even the smallest incident happened, regardless of the hour (shift work) and the rule was quickly repealed.

- We were able to get all workers along to paid ‘team meetings’ outside shift hours, rather than the previous case where the boss would with one section of workers as individuals during their shift.

- We were able to open up discussion around some of the attempts by the boss to split workers through racist rhetoric. ‘Those workers are x, therefore they x/banning the use of ‘auntie/uncle’ – She even used the classic ‘I’m not racist but..’. A few fellow work-mates had previously accepted this rhetoric, but through opening it up to discussion we were able to counter some of its effects.

- For the section of subcontracted foreign workers it was a stressful game trying to get the correct pay – it’d be 6 or 7 back and forth emails to explain why between $20-100 was missing from the paycheck, or why pay would come in on Friday instead of Tuesday. No one wants to have to constantly check their bank account and do the maths to make sure they got paid correctly. By getting everyone to collectively write to the employer threatening action this micky mouse game ceased (at least for a while). We also secured a small pay-rise for some of the foreign workers who were being unknowingly underpaid.

- It’s a fine balance and some came to the conclusion that the job just wasn’t worth it. Eventually one fellow-worker (a staunch organiser) employed by the security subcontractor was fired for breaking a bogus 3 month parole period (a concession that we secured when they first tried to fire him). In response all the other 4 workers under that sub-contractor walked off the job mid-shift and deleted data off all the computers (sabotage). To go along with this we collectively wrote a letter outlining all the dodgy practices of the management and the subcontractor and sent this out to the entire company. The four who walked out decided to never come back to work.

The group has ebbed-and-flowed in activity, mostly due to the casual nature of the workforce and frequent change in workers. The culture of solidarity has had to be constantly rebuilt & reinforced, partly through sharing the work site’s history with new workers. At the time of writing we are currently meeting once a fortnight around multiple issues, including unpaid/stolen wages, disciplinary meetings, and the unfair dismissal of one of our work-mates mentioned above. One promising development has been inviting workers from other workplaces but in the same industry to these work-group meetings to share our experiences. Although the above example may seem small and insignificant (and still remains largely informal and covert), I think it’s important that we share our nuts and bolts attempts. I see this kind of organising work as the foundation for broader anarcho-syndicalist union activity; federations of work groups and industrial networks from the bottom up.

“We need to organise struggles ourselves along direct action lines. And if we’re not capable of doing so at present, we need to aspire to that capability; we need to move from being a political propaganda group to being a revolutionary union. The Solidarity Federation describes itself as a revolutionary union initiative to signify this intent. So far, the struggles we have initiated have been small scale and often focussed on individual grievances. But that merely reflects the limits of our present capacities, capacities we are always seeking to expand. Specific political organisation is not sufficient to this task. We seek to become an organisation which is at once political and economic. – From ‘Fighting for Ourselves’ (Solidarity Federation)

See also: Informal Work Groups (IWW)