Apr 6, 2015

Lynch your Landlord: An Interview with Seattle Solidarity Network

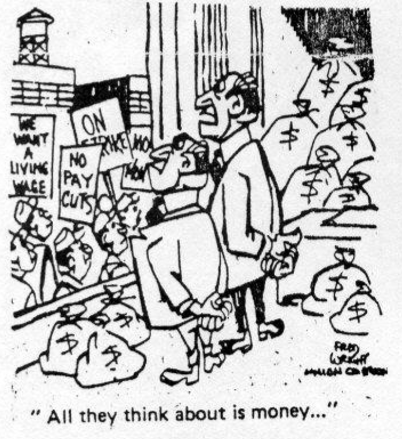

I did this interview a while back with a Seattle Solidarity Network organiser. What are Solidarity Networks? The ‘Solidarity network’ is one way of organising which has the potential for dual power. In a nutshell, they are networks which span across different communities and different workplaces (regardless of unions or not), in order to support and connect struggles and build collective action. The principles behind solidarity networks rely on the balance of class forces, and recognise that sometimes we have to fight defensively because as a class we are weak, and this can’t be compensated for by small group actions ‘attacking’ back in whatever way (e.g. networks don’t firebomb dodgy real estates, they organise tenants to collectively assert their needs, even if that’s only defensively enforcing basic standards, because this builds the capacity, confidence and culture from which more ambitious demands can be made.)

I did this interview a while back with a Seattle Solidarity Network organiser. What are Solidarity Networks? The ‘Solidarity network’ is one way of organising which has the potential for dual power. In a nutshell, they are networks which span across different communities and different workplaces (regardless of unions or not), in order to support and connect struggles and build collective action. The principles behind solidarity networks rely on the balance of class forces, and recognise that sometimes we have to fight defensively because as a class we are weak, and this can’t be compensated for by small group actions ‘attacking’ back in whatever way (e.g. networks don’t firebomb dodgy real estates, they organise tenants to collectively assert their needs, even if that’s only defensively enforcing basic standards, because this builds the capacity, confidence and culture from which more ambitious demands can be made.)

Networks try to bring anyone affected by an issue together to collectively discuss the issue. The key is the self-activity of all of those concerned, to widen the fight, and encourage a state of permanent dialogue, planting the seeds for ongoing, relevant forms of organising which empower all of those affected; not just network members, but those who aren’t members of the network and who may never want to be.

Meaningful action, for us is whatever increases the confidence, the autonomy, the initiative, the participation, the solidarity, the equalitarian tendencies and the self-activity of the people and whatever assists in society’s demystification. Sterile and harmful action is whatever reinforces the passivity of people – our apathy, our cynicism, our differentiation through hierarchy, our alienation, our dependence on others to do things for us and the degree to which we can therefore be manipulated by others – even by those allegedly acting on our behalf.

Q: Could you tell us a bit about yourself and how you became involved with SEASOL?

Note that I’m not speaking for the organisation, just as an individual participant. I personally got involved as one of the five Wobblies (IWW members) who started SeaSol at the end of 2007. I had been a believer in anarcho-syndicalism since my early teens.

I had spent three years in Montreal among radical activists during early 2000’s, when a lot was happening, e.g. the Quebec City demonstrations and strong anarchist and student movements growing in the wake of that. Then back home in North Carolina, I had been involved in fairly radical ‘minority union’ activity with a union called UE, organizing with fellow state employees, from cleaners and mechanics to secretaries and nurses. From that experience I got a strong sense of the potential and need for worker organizing beyond the boundaries of standard unionism.

After I moved to Seattle in late 2005, I gradually found a small group of like-minded Wobblies who wanted to make something happen, so we started meeting and discussing ideas, and in winter 2007/2008 SeaSol was born.

Q:What’s Seasol’s about? Could you give us an overview of how actions are organised?

Seasol is a network of volunteers, open to workers employed and unemployed, active and retired, who believe in building solidarity, standing up for our rights and improving our conditions. We don’t have formal membership, but our action-announcement email list currently has 300 people; our phone tree has about 120 people; and our organising committee is 11 people. Each week someone volunteers for ‘secretary duty’, which means they take responsibility for handling the calls that week.We operate on very little money. We just don’t need much. We have no paid staff.

When SeaSol is first approached by someone with a conflict or grievance, two or three of our more active volunteers (which we call ‘organizers’) set up a meeting with them, usually at a coffee shop. At that meeting we listen to the story, clarify what the problem is and what the demands might be, explain the basics of how SeaSol works, and find out if the person or people we’re talking to would want to join with SeaSol in fighting for their demands. We also mentionthat we would like for them to be willing to stay in touch with SeaSol (i.e. be on our phone tree) and participate in future actions in support of other workers and tenants. SeaSol then makes a democratic decision about whether or not we are going to take on this particular fight.

This can happen either by vote at our weekly meeting, or between meetings via our ’24-hour rule’. The ’24-hour rule’ is sort of a passive consensus process for quick decisions between meetings. One of the organizers emails all the others and says “I propose that we agree to get involved in this fight.” If none of the others expresses disagreement within the next 24 hours, then the proposal is considered passed. There’s more to this process and to the ‘organizer’ role that might be worth explaining/discussing, but for now I won’t bore you with any more details on this.

– After we’ve decided to get involved in a particular conflict, then whenever possible the planning and decision-making for the action campaign takes place within our regular weekly meetings. We often do ‘break-out’ sessions within our meetings, where the meeting splits up into 2 or 3 groups for 30 minutes or so, to carry out the detailed planning for multiple fights and/or other projects, and then we reassemble so each sub-group can report back, and take votes if there are things that need to be decided by the group as a whole.

Our first action is almost always a demand-delivery action. A group of people, usually somewhere between 10 and 30 (or as many as we can muster) goes to confront the employer/landlord in person, and their employee[s]/tenant[s] hands them a piece of paper that spells out the demand. The demand letter usually includes a time limit for meeting our demands, after which we will take further action. It also includes our web address, so they can see what kinds of things are likely to happen if they don’t give in. Once the demand has been delivered and we’ve taken some photos, we leave.

Then we start planning an ongoing series of actions aimed at pressuring the employer/landlord, usually by hurting their business, until the demands are met. Sometimes we picket, with “Don’t shop here” signs. A few times we stood outside a restaurant and gave out coupons for a nearby competitor. Sometimes we cause social embarrassment by visiting all their neighbors and distributing flyers where they live.

Or we pressure other businesses/institutions into cutting ties with them. Sometimes we spread information online and with posters to warn tenants not to rent from a particular landlord. Or we visit all the tenants and encourage them to file a barrage of complaints about health violations. Twice we’ve had groups of tenants who were facing eviction, and we helped organize them to form a pact and announce that none of them would leave the place (i.e. the landlord would have to go through the lengthy and costly process of forcibly evicting every one of them) until all of them received money from the landlord to help them get a new place.

Once we continually pressed the pedestrian “cross” button and kept slowly crossing and re-crossing the street to create a big traffic jam at the entrance to a supermarket parking lot. These are just some examples. They come up with tactics that cause the most possible harm to the employer/landlord with the least harm/risk to our people.

Q: Has SEASOL ever experienced violent attacks from landlords or bosses? How are police and other groups dealt with?

We’ve only ever experienced threats and very minor violence. I once got a threatening anonymous email, where a slumlord had paid for a little ‘background investigation’ on me and included a bunch of semi-accurate personal info to scare me. Once we had threats that a worker would get jumped if we kept picketing. We kept picketing, but took care to make sure we had a sizable group and stayed together at all times. Another time someone snatched and broke some of our picket signs. We started taking pictures of the guy (a young manager-in-training) and he ran away.

The cops often get called to our actions (the bosses call them), but so far we have generally stayed within the letter of the law, and we’ve been able to persuade the cops to leave us alone. We always delegate one person to be the ‘coptalker’ for the action, which helps prevent unnecessary trouble. Cops are always more comfortable if they think the group they’re dealing with has a leader, so we let them imagine the ‘cop-talker’ is our leader, when in fact they have no more authority than anyone else. Staying within the law is a strategic/tactical decision for us, given our current weakness.

Loren Ruud was my landlord. The apartment had bedbugs in it. I tried to get rid of them, I bombed it three times, but I couldn’t get rid of them. It was an old apartment. The place wasn’t up to code. It was terrible. I had to call a crisis hotline. I also had to call the housing authority, because the apartment had bedbugs, it had an unsecured door, and it had dry rot in the kitchen. And as soon as Ruud found out that I had called the city, he came up to my place on Thanksgiving with no notice, and threatened to evict me.

The housing inspectors rescinded the ten-day notice, since Ruud was trying to retaliate against me. They decided that I should vacate by December 20th and the landlord should pay me $1,000. I vacated December 17th. I left the place clean and tidy. Then Ruud decided to come after me for$1800 in “damages to the apartment”.

I called my friend Nohl, and he told me what he knew about Seattle Solidarity. He had gotten one of their flyers at the Martin Luther King Jr day march. I called Seasol, left a long message, and sent an email, and thenI met with Kaleen, Lee and Ryan at Bedlam Coffee.

We delivered a demand letter to Ruud, saying: rescind the charges of $1800, don’t send it to collections, and “leave John alone.” We waited two weeks, and there was no response to the letter. Then we decided to poster the place. The posters said “Beware: do not rent from 9632 Aurora Ave N- environmental sickness, bedbugs, dry rot…”

The strategy was to let the people in the area know about the conditions in those apartments, and that the landlord steals deposits and rents out substandard housing.On a Thursday, one week after postering in Loren Ruud’s neighborhood, he called me and said “please stop what you’re doing. If you and Seattle Solidarity stop your actions against me, I will not send the $1800 tocollections.” And we agreed.

And that was it. The corporations don’t want to pay out anything to workers, and the landlords don’t want to pay to maintain apartments, so they’re trying to pass all the costs onto their tenants. There’s a great need for Seattle Solidarity. In me, they now have a good volunteer.